Empty Nose Syndrome Treatment Options

Non-surgical treatment options are meant to maintain and slightly improve the health of the remaining nasal mucosa in the ENS nose, by keeping it moist and free as possible from irritation and infection.

Surgical treatment is meant to try to permanently improve the severity of the symptoms.

Non-surgical ENS Treatment

Non-surgical treatments will not cure ENS, because it cannot restore the missing turbinates, but it can help control some of the symptoms and make the suffering more tolerable:

- Daily nasal irrigations of regular saline are always recommended. Many patients prefer to use Ringer’s Lactate solution instead, as they find it’s easier on the mucosa than regular saline, and there are some empirical studies that back up that claim.

- Saline, Ringer’s Lactate, or hyaluronic acid based – nasal mist sprays, or gels, are always helpful when proper irrigation is not possible.

- Sesame oil can help in cases of extreme dryness and crusts.

- Drinking lots of hot soups and beverages. Caffeine is best avoided.

- Sleeping with a cool mist humidifier.

- Sleeping with a CPAP machine that has a built-in humidifier.

- Acupuncture and shiatsu meant to improve nasal blood supply and nerve function.

- Dressing warmly and sleeping in a warm environment.

- Regular physical activity and a healthy life style are most important too.

Surgical ENS Treatment

The underlying rational of surgery is to restore the inner nasal geometrical structure of the nasal passages of air (the inferior, middle and superior meatuses).

Turbinate tissue is unique and there are no potential donor sites in the body to harvest similar tissue from. However, in the nose, Form = Function. It is therefore possible to restore some function by restoring the natural contours and proportions of the nasal passages: It is possible to create an artificial look alike structure of a turbinate in the nasal cavities, and thus – to regain some of the nose’s capabilities to adequately pressurize, streamline, heat, humidify, filter and sense the airflow.

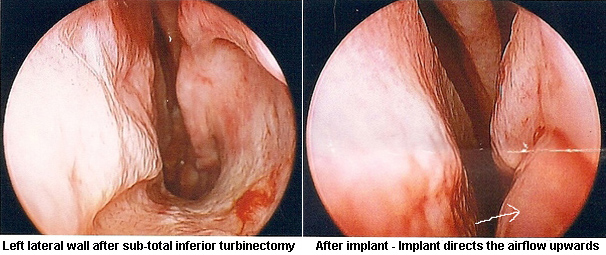

By implanting different grafts and material underneath the patients’ submucosa at the right places – the surgeon hopes to create a look alike turbinal structure which will do four things:

- Restrict the amount of airflow, just enough to allow the nasal mucosa to cope better, while still allowing enough air to pass through for all needs of breathing. This is referred to as normalizing the nasal rates of resistance.

- Restore close to normal rates of nasal mucosal heat and humidity, as the implant projections trap the heat and moisture in the air returning from the lungs.

- Normalize the post surgical disrupted airflow patterns of the nose and make sure that the vast majority of airflow is redirected into the middle meatus of the nose.

- Increase the mucosal surface in the nose that comes in contact with the airflow. This increases airflow sensation, amongst all the other things that are mentioned above that help improve the sensation too.

Implant Materials for ENS

The bulking up of the sub-mucosa and mucosa to create a neo-turbinate structure can be achieved through implanting some supporting material between the bone/cartilage and the submucosal layer. Many materials have been tried over the past 100 years. In most cases this operation was used to restore heat and humidity to atrophic noses.

Generally speaking – the implant materials can be divided into 3 groups:

autografts: bone, cartilage, fat, etc’ from one site to another in the same patient. The problems here are relative shortage of tissue, and long term studies have shown high absorption rates in the nose.

foreign materials: such as – hydroxyapatite, fibrin glue, Teflon, gortex, and plastipore, which solve the shortage problem of autografts, are easy to shape and don’t tend to get absorbed. However they have a high extrusion rate, and sometimes cause infection.

allografts: In the last decade scientists have been able to harvest and remove away genetic markers of some basic human tissues (like skin dermis) from donors, and thus supplying a human natural implant material which will not stimulate the immune system to reject it. A good example for such material is acellular dermis (brand named – “Alloderm”). It does not get rejected and in most areas retains most of its volume over long periods.

Alloderm implants have already been implanted successfully for a few years now in a small but growing number of ENS patients. At four years follow-up, results seem stable and encouraging. It seems that Alloderm implants cannot fully cure ENS but can help alleviate much of the suffering, with various degrees of success, depending on the individual condition of each patient.

The ideal implant material, other than real original turbinate tissue should be something with low extrusion and rejection rates, minimal infection risk, and very importantly – that will provide a strong and endurable enough structure and at the same time allow good permeability for blood vessel incorporation, which seems to be the key against long term absorption.

The following is a short video demonstrating Alloderm implantation to create a septal neo-inferior-turbinate in a cavity where the original IT was completely resected and of augmenting a partially reduced inferior turbinate in the other cavity with adding some Alloderm strips to it. Performed by Dr Steven Houser:

What Lies Ahead For ENS Sufferers

A 100% complete cure will only be available if and when the situation is reversed and the actual real tissues of the resected turbinates are regenerated or returned to the nose through means of regenerative medicine and/or tissue-engineering. The technology and know-how knowledge of how to do so exist. The application, like in so many other physical disorders, is another matter altogether.

Hopefully tissue engineering and regenerative scientists will begin to take more interest in functional inner nasal reconstruction, as the complication rates of functional nasal surgery are amongst the highest rates compared to most other types of elective surgery.

Citations From Medical Literature

“The symptom that most often indicates ENS is paradoxical obstruction: subjects may have an impressively large nasal airway because they lack turbinate tissue, yet they state they feel they cannot breathe well. There is no clear way to describe the breathing sensation that patients with ENS experience. Some patients may state that their nose feels “stuffy,” for lack of a better word, whereas others state their nose feels too open, yet they cannot seem to properly inflate the lungs; they feel they need some resistance to do so. Patients with ENS do not sense the airflow passing through their nasal cavities, whereas their distal structures (pharynx, lungs) do detect inspiration; the patients’ central nervous systems receive conflicting information. These patients seem to be in a constant state of dyspnea and may describe the sensation of suffocating. The constant abnormal breathing sensations cause these patients to be consistently preoccupied with their breathing and nasal sensations, and this often leads to the inability to concentrate (aprosexia nasalis), chronic fatigue, frustration, irritability, anger, anxiety, and depression.”

(Houser SM. Surgical Treatment for Empty Nose Syndrome. Archives of Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery\ Vol 133 (No.9) Sep’ 2007: 858-863).

“…The excess removal of turbinate tissue might lead to empty-nose syndrome. Excess resection can lead to crusting, bleeding, breathing difficulty (often the paradoxical sensation of obstruction), recurrent infections, nasal odor, pain, and often clinical depression. In one study, the mean onset of symptoms occurred more than 8 years following the turbinectomies.”

(From: “The turbinates in nasal and sinus surgery: A consensus statement.” By D. H. Rice, E. B. Kern, B. F. Marple, R. L. Mabry, W. H. Friedman. ENT – Ear, Nose & Throat Journal, February 2003, pp. 82-83.)

“Turbinate Reduction and Resection:

Unfortunately, a wide nasal cavity syndrome due to reduction or resection of the inferior turbinate (and/or middle turbinate) is still frequently seen. When caused by (subtotal) turbinectomy, it can hardly be considered a complication. In our opinion, it is a “nasal crime”. This iatrogenic condition can easily be avoided by reducing a hypertrophic turbinate using one of the intraturbinal function-preserving techniques.”

(From: “Functional Reconstructive Nasal Surgery”. By Egbert H. Huizing, John De Groot. Hard-cover publication by Thieme, 2003. page 285).

“Empty nose syndrome: Some patients who have had excision of the inferior and/or middle turbinates may report increased symptoms thereafter. They may report a reduction in nasal mucus, nasal dryness or sensation of nasal obstruction or blockage and a general reduction in their sense of well-being.

Out of concern for this problem, many surgeons are now reluctant to perform any significant amount of surgical turbinectomy. As a result, preservation of as much turbinate tissue as is possible is now considered by many to be an important part of surgical management. Many surgeons will only remove a very small portion of the middle turbinate if absolutely necessary in order to achieve adequate visualization or to remove devitalized tissue. Operative descriptions of the extent of resection may be variable, and the endoscopist should make an independent assessment of the amount of resection performed. Radiofrequency ablation of the turbinates (e.g. Somnoplasty) has not caused the same problems as surgical turbinate reduction.”

(Wellington S. Tichenor, MD; Allen Adinoff, MD; Brian Smart, MD; and Daniel Hamilos, MD. The American Academy of Allergy Asthma Immunology Work Group Report: Nasal and Sinus Endoscopy for Medical Management of Resistant Rhinosinusitis, Including Post-surgical Patients November, 2006. Prepared by an Ad Hoc Committee of the Rhinosinusitis Committee.)

“Removal of an entire inferior turbinate for benign disease is strongly discouraged because removal of an inferior turbinate can produce nasal atrophy and a miserable person. Such people unfortunately are still seen in the author’s offices; these people are nasal cripples.”

(From: “Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery”, Page 496, chapter 23. Chapter written by Dr. Kern. Book by Dr. Meyyerhoff and Dr. Rice, published by the W.B. Saunders Company, 1992).

“Total inferior turbinectomy has been proposed as a treatment for chronic nasal airway obstruction refractory to other, more conservative, methods of treatment. Traditionally, it has been criticized because of its adverse effects on nasophysiology. In this study, patients who had previously undergone total inferior turbinectomy were evaluated with the use of an extensive questionnaire. It confirms that total inferior turbinectomy carries significant morbidity and should be condemned.”

(from “Extended Follow-Up Of Total Inferior Turbinate Resection For Relief Of Chronic Nasal Obstruction”, G. F. Moore, T. J. Freeman, F. P. Ogren & A. J. Yonkers., Laryngoscope, September 1985, pp. 1095-1099.)

“… The inferior turbinal should never be entirely removed… Excessive removal allows a jet of inspired ventilation, the mucus evaporates and becomes so viscid as to impede ciliary action… In some cases where the inferior turbinal has been too freely removed, the loss of valvular action and undue patency of the nostril produce the discomfort of dry pharyngitis and laryngitis, with difficulty in expelling stagnant secretion from the nose. The loss of the turbinal may lead to a condition simulating atrophic rhinitis or even ozaena.”

(Thomson St. C & Negus VE. Inflammatory diseases. Chronic Rhinitis. Diseases of the nose and throat, 6th edition. London: Cassel & Co. Lmt. 1955; 124-145).

“… Resistance to air currents on inspiration and during expiration is necessary to maintain elasticity of the lungs.”

(Cottle MH. Nasal Breathing Pressures and Cardio-Pulmonary Illness. The Eye, Ear Nose and throat Monthly. Volume 51, September 1972.)

References

1.Rice, Kern, Mabry, Friedman. The turbinates in nasal and sinus surgery: A consensus statement. Ear Nose & Throat Journal, Feb’ 2003.

2.Meyyerhoff & Rice. Otolaryngology– Head and Neck Surgery. Page 496, chapter 23. Chapter Written by EB Kern. Published by the W.B. Saunders Company, 1992.

3.Huizing & de-Groot. Functional Reconstructive Nasal Surgery. Pages 285 – 288: Surgery of the Wide Nasal Cavity. Published by Thieme. 2003.

4.Houser SM. Surgical Treatment for Empty Nose Syndrome. Archives of Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery\ Vol 133 (No.9) Sep’ 2007: 858-863.

5.Thomson St. C & Negus VE. Inflammatory diseases. Chronic Rhinitis. Diseases of the nose and throat, 6th edition. London: Cassel & Co. Lmt. 1955; 124-145

6.Elad D, Naftali S, Rosenfeld M, Wolf M. Physical stresses at the air-wall interface of the human nasal cavity during breathing. J Appl Physiol. 2006 Mar;100(3):1003-10.

7.Swift AC, Campbell IT, Mckown TM. Oronasal Obstruction, Lung Volumes, And Arterial Oxygenaytion. The Lancet. January 1988, pages 72-75.

8.Cottle MH. Nasal Breathing Pressures and Cardio-Pulmonary Illness. The Eye, Ear Nose and throat Monthly. Volume 51, September 1972.

9.Milicic D, Mladina R, Djanic D, Prgomet D, Leovic D. Influence of Nasal Fontanel Receptors on the Regulation of Tracheobronchal Vagal Tone. Croat Med J. 1998 Dec;39(4):426-9.

10.Berenholz L, et al’. Chronic Sinusitis: A sequela of Inferior Turbinectomy. American Journal of Rhinology, July-August 1998, volume 12, number 4.

11.Grutzenmacher S, Lang C and Mlynski G. The combination of acoustic rhinometry, rhinoresistometry and flow simulation in noses before and after turbinate surgery: A model study. ORL (Journal) volume 65, 2003, pp 341-347.

12.Passali D, et al’. Treatment of hypertrophy of the inferior turbinate: Long-term results in 382 patient randomly assigned to therapy. by in Ann’ Otol’ Rhinol’ Laryngol’, volume 108, 1999.

13.Chang and Ries W. Surgical treatment of the inferior turbinate: new techniques: in Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, volume 12, 2004 (pp 53-57).

14.Moore GF, Freeman TJ, Yonkers AJ, Ogren FP. Extended follow-up of total inferior turbinate resection for relief of chronic nasal obstruction. by in Laryngoscope, volume 95, September 1985.

15.Oburra HO. Complications following bilateral turbinectomy. East African Medical Journal, volume 72, number 2, February 1995.

16.Houser SM. Empty nose syndrome associated with middle turbinate resection. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006 Dec;135(6):972-3.

17.May M, Schaitkin BM. Erasorama surgery. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, 2002, volume 10, pp: 19-21.

18.Wang Y, Liu T, Qu Y, Dong Z, Yang Z. Empty nose syndrome. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi. 2001 Jun;36(3):203-5.

19.Moore, E.J. & Kern, E.B. (2001). Atrophic rhinitis: A review of 242 cases. American Journal of Rhinology, 15(6)